Finnish often appears on the lists of hardest languages to learn for English speakers. In this post, I am going to discuss different aspects of the Finnish language and their difficulties. Of course, each individual finds different things to be difficult. What follows are simply based on my own experience of learning Finnish.

Pronunciation

Finnish pronunciation is pretty simple; Finnish has fewer native sounds than the surrounding Indo-European languages. I find Finnish pronunciation to be very precise: each sound almost always sounds the same. In other words, there are very few allophones, unlike in English. The "t" sound in English can sound very different based on where it lies in a word:

- tin: aspirated "t"

- water: flapped "r"

- button: glottal stop

In Finnish, there are few of these pronunciation subtleties, so it is not difficult to master. On the other hand, consonant and vowel length are very important, unlike in English. My grammar textbook (Finnish: An Essential Grammar) gives this example:

Sometimes, long sounds come after each other consecutively and repeatedly, for example: liikkeessään, "in his/her/their shop." These can be awkward to pronounce.

I initially found many Finnish diphthongs to be awkward to pronounce as well, including yi, äi, öi, ey, äy, öy, and yö. You get used to these quickly, though.

Alphabet/Orthography

Finnish orthography was designed so that one sound matches to one letter nearly perfectly, making reading and writing words very easy. Once you learn the alphabet, you can write any word after hearing it. Also, you can pronounce any new word perfectly, making learning vocabulary easier as well.

Grammar

Here is where Finnish gets its reputation for being a difficult language. Before you can inflect a Finnish word, you need to know vowel harmony, consonant gradation, vowel changes, as well as many different patterns of inflection for both nouns and verbs. Vowel harmony is actually pretty simple, but consonant gradation can take a while to get used to. When suffixes are added to words, sometimes consonants alternate between strong and weak forms, depending on the suffix. When you see a new word, you cannot always know for sure if it gradates.

- katu ("street") -> kadut ("streets")

However:

- auto ("car") -> autot ("cars")

Consonant gradation becomes difficult to wrap your head around when certain words gradate backwards. This usually happens when inflecting a word derived from another word, or from a word that ends with a consonant.

- koe ("test") -> kokeet ("tests")

- hammas ("tooth") -> hampaat ("teeth")

Vowel changes that occur before suffixes can be simple, but when applied to nouns with 3 syllables, the rules become so complex that there's almost no use memorizing them, and it's better to just memorize what vowel changes happen in each word you learn.

There are 6 verb inflection types. Basic verb conjugation is actually pretty simple, because personal suffixes are the same for all 6 types. However, some forms such as the passive can be tricky. Luckily there are very few irregular verbs.

Finnish nouns inflect in 15 cases, something that many tend to freak out about. However, cases in Finnish are not like cases in Latin. The plural forms and singular forms are based on the same suffix, and most of the cases are added to words in exactly the same way, making them almost like postpositions. Plus, 3 cases are rarely used except in fixed expressions. In addition, Finnish has no gender to worry about.

There are technically 51 different inflection types recognized by KOTUS (the Finnish government institute for language), but the number makes it sound much harder than it really is. These "types" do not have entirely different endings, as mentioned above. Almost all of the case endings are consistent, except a few that may vary a little depending on which inflection type a word follows. About 15 of the 51 types are rare or very rare, and many are almost identical to each other. Two of the types are just redundant rules for compound words, so the number of types you need to worry about is reduced greatly.

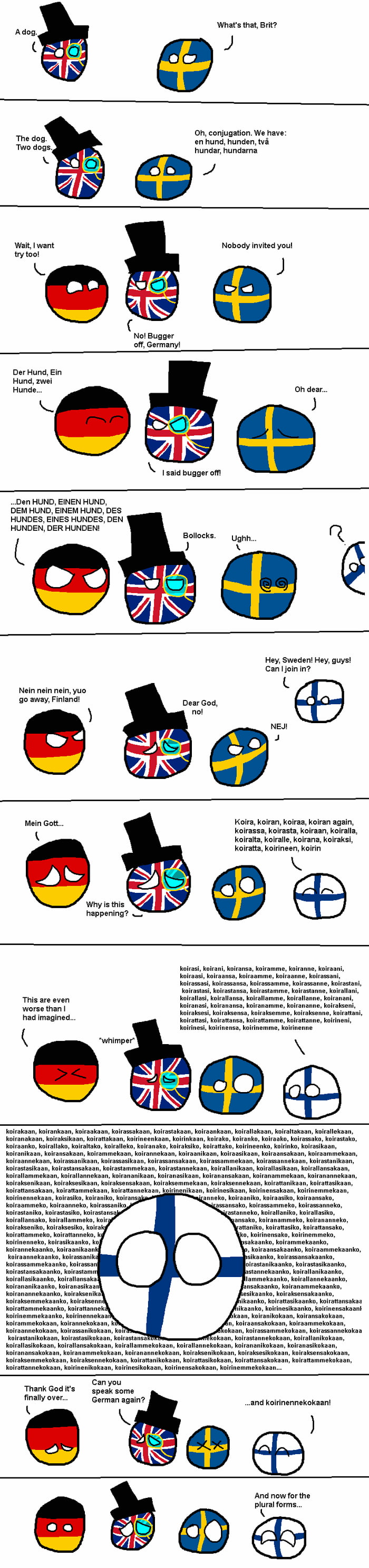

Finnish grammar is not as difficult as some make it out to be. There are popular posts that have circulated through the Internet that show examples of the Finnish language that makes it seem absolutely ridiculous.

Like I mentioned before, Finnish inflection isn't like inflection found in most other European languages. The difficulty in Finnish inflection is usually not the endings, but rather the changes in the base word. For the most part, endings are so easily and logically attached to a word that they barely even be considered to create "new forms" of a word like the comic above suggests.

Other posts show extremely long Finnish words like epäjärjestelmällistyttämättömyydelläänsäkäänköhän, but even a native speaker will find it hard to explain what that even means. Words like these are never used in daily speech or writing.

Even though Finnish grammar is definitely difficult, it's best to simply learn it without worrying too much about difficulty.

Vocabulary

As Finnish is not an Indo-European language, most basic words will seem alien. That isn't to say that Finnish doesn't have loanwords from other European languages; it has many. However, many old loanwords were altered so that they followed the native Finnish sound system. This makes them seem just as alien as native Finnish words (for example, Swedish strand "beach" was borrowed into Finnish as ranta). This may prove difficult for learners of popular European languages (French, Spanish, German, etc.) who are used to inferring meaning when reading or listening to a new target language.

Luckily for the learner, recently there has been a large influx of English words, and more recent loanwords in general haven't been altered the same way old loanwords have, making them much more similar to the original words. Another positive is that Finnish has many productive suffixes that make learning related vocabulary easy.

- kirja "book"

- kirjallinen "literary"

- kirjallisuus "literature"

- kirjasto "library"

- kirjanen "booklet"

- kirjasin "font"

- kirjata "to book"

- kirjoittaa "to write"

- kirje "letter"

Standard vs. Colloquial Language

While all languages have some difference between the standard language and the colloquial language, the difference in Finnish can be quite vast.

"Did you know that we have already eaten?"

Standard Finnish: Oletko sinä tiennyt, että olemme jo syöneet?

Colloquial Finnish: Ooksä tienny, et me ollaan jo syöty?

"We were there for twenty-four hours."

Standard Finnish: Olimme siellä kaksikymmentäneljä tuntia.

Colloquial Finnish: Me oltiin siel kakskytnel tuntii.

The grammatical rules from a textbook don't always stay true when people speak and write colloquially. Certain consonants and vowels are dropped, pronoun use changes, and some common verbs have shortened forms. These changes vary between speakers and dialects. If one only studies formal Finnish, they will be very lost when faced with the language used in daily conversations and on the Internet. However, after learning some of the common differences in colloquial language and being exposed to it (especially through the Internet), using it yourself isn't that difficult. It makes sense that a grammatically complicated language would have a somewhat simplified colloquial form.

Resources

Finnish would not be as difficult as it is if it were a more popular language. Popular languages such as Spanish, French, German, and Japanese have plenty of language learning resources. Finnish, on the other hand, only has around 5 million speakers, and isn't exactly the most useful language in a global context. Finding resources for learning Finnish can be difficult, especially for more advanced learners. It is also hard to find any other learners (or native speakers) to practice with if you aren't living in Finland.

Conclusion

Finnish can definitely be bewildering for a native English speaker or anyone only used to Indo-European languages. However, difficulty is subjective. Perhaps you may find the logic and regularity of Finnish grammar refreshing compared to the seemingly arbitrary rules found in many European languages. If you are interested in a language, it is best to just learn it without worrying about its difficulty.

Feel free to share your thoughts in the comments about Finnish difficulty.